Perhaps there was something of Giddens’s paradox at play with plastic pollution. Giddens’s paradox describes phenomena, like climate change, where people don’t take adequate action until the problem is visible and acute – by which time it’s already too late.

Around 11 million metric tons of plastic waste enter our oceans every year. This is a staggeringly large amount. It’s so large that it is nearly impossible to imagine – even if converted into jumbo jets (it’s the same as about 60,000 Boeing 747s) or broken into smaller time periods (it’s over 1,200 metric tons flowing into the ocean every hour).

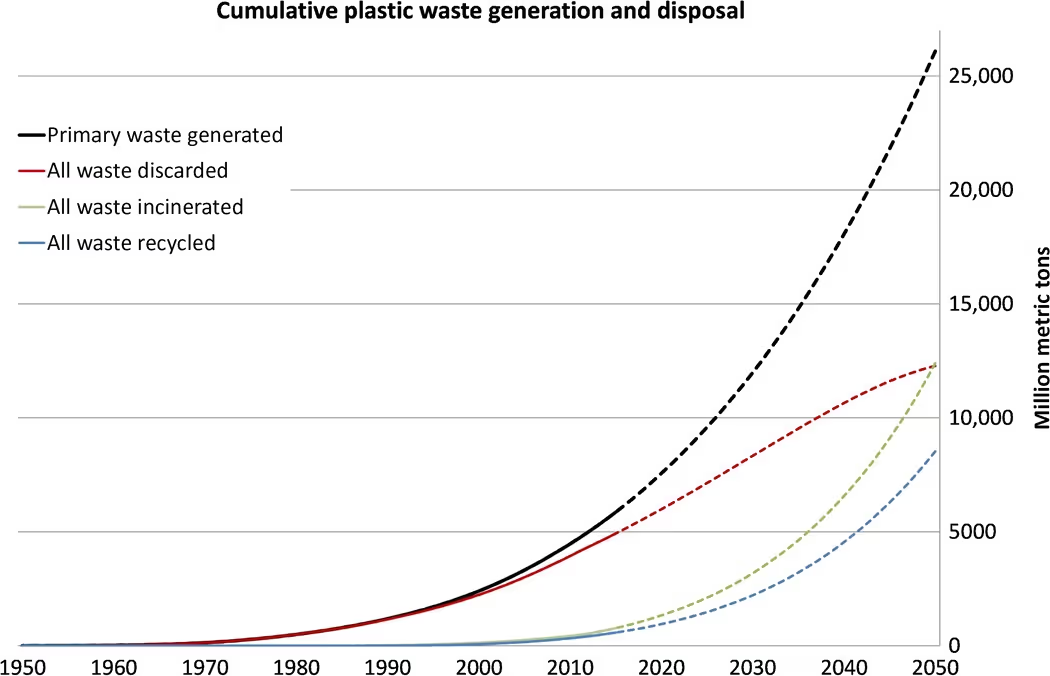

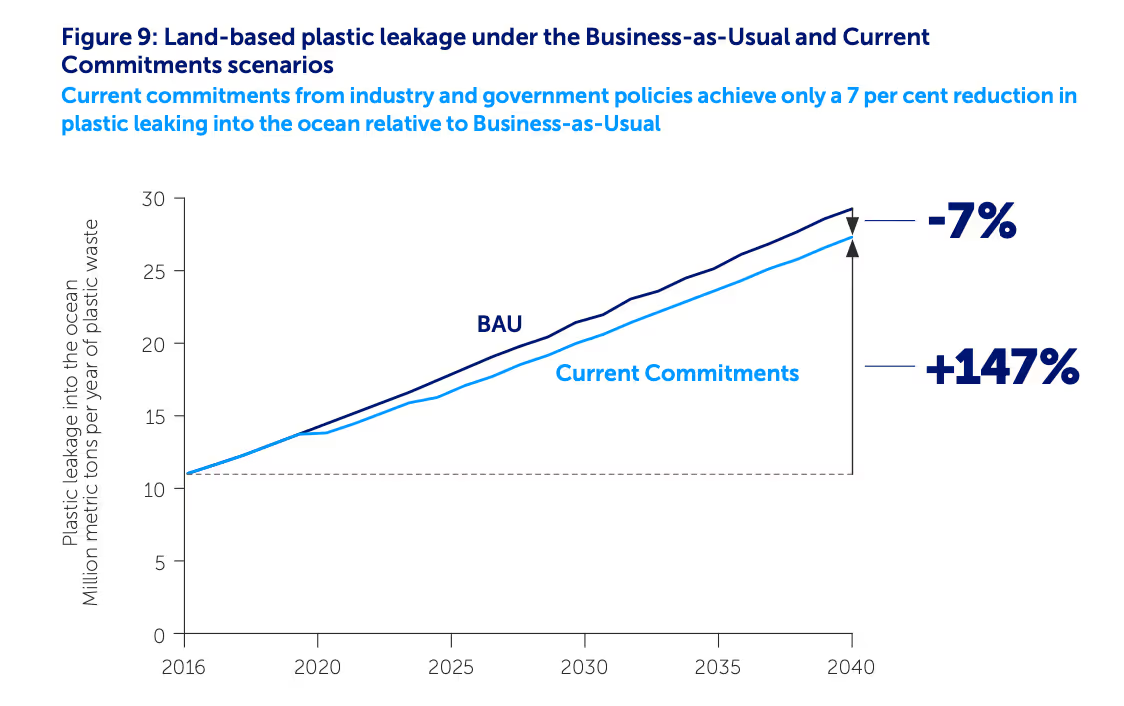

This huge amount of pollution is the result of our seemingly unquenchable demand for plastic, and our ongoing failure to manage waste effectively. Global plastics production doubled from 2000 to 2019 but 40% of today’s global plastic waste ends up in the environment. By 2040 it’s estimated there will be four times as much plastic stock in the ocean as there is today, unless significant changes are made.

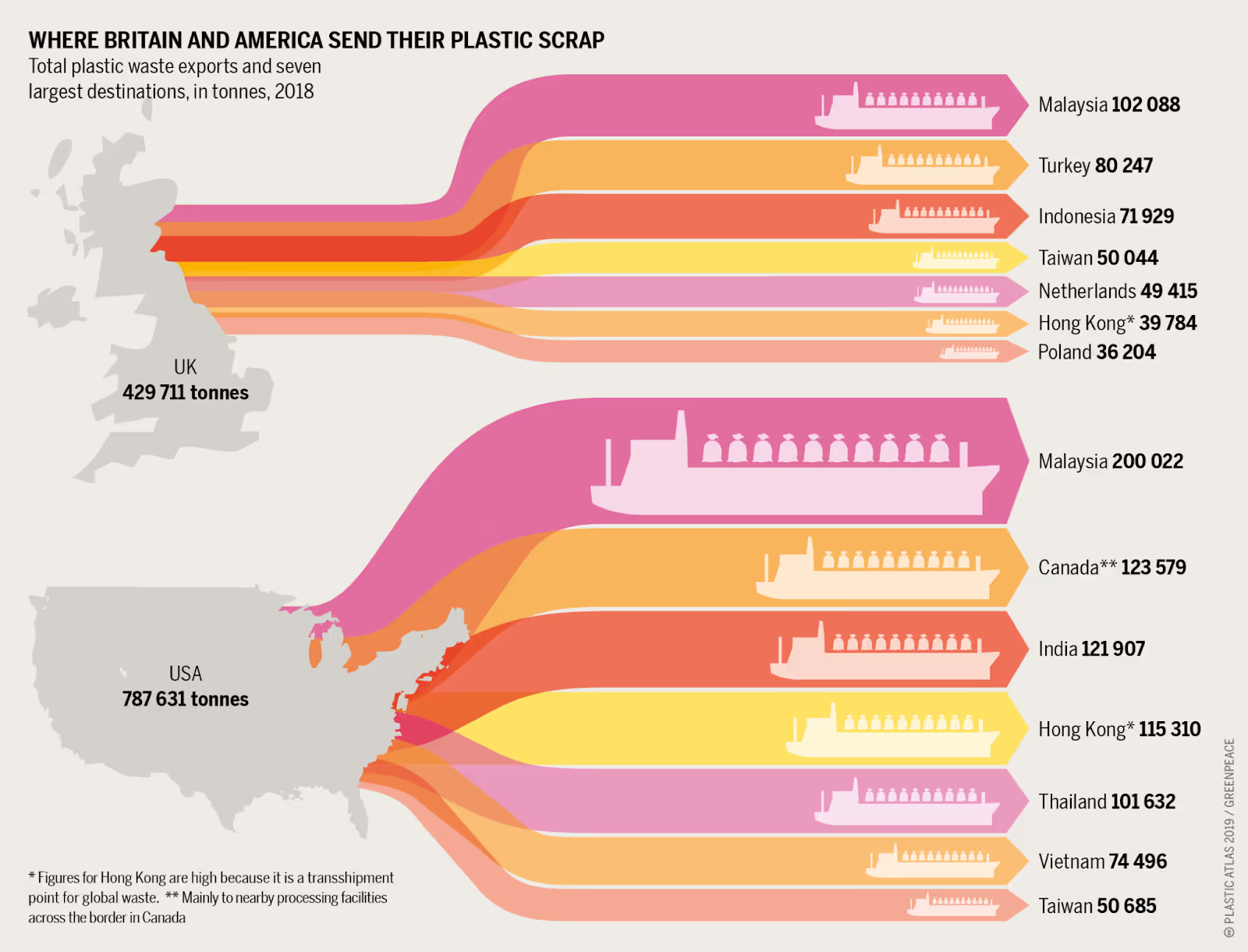

But despite the frightening statistics, significant changes are not happening at the required speed. Perhaps this is where the visibility of the problem has played a role. In the UK and USA, plastic is removed from homes and businesses and largely hidden from sight. In fact, often it is removed from the country, and exported to countries with their own waste management challenges. This is not the case in other parts of the world, and perhaps our efforts to curb plastic use would have started earlier – and Giddens’s paradox avoided – if our excessive use of plastic had led to waste piling up on North American streets, choking European ecosystems, or polluting UK beaches to the extent it has elsewhere.

Developed economies like the UK and USA have historically used more plastic than other parts of the world, continue to have the largest per capita plastic footprints, and still are failing to deal with the plastic waste that they are generating.

As the plastic waste crisis continues to escalate, it is having a profoundly damaging but unequal effect on human and environmental health. Developing economies are dealing with the brunt of the issue. Is there, perhaps, a case for plastic waste reparations?

There are solutions emerging that enable action on the plastic waste issue. There are new regulations being introduced, ongoing efforts to reduce and replace virgin plastics in packaging, and money from plastic producing brands in developed economies can be channelled to support the creation of infrastructure where it is most needed. These developments provide hope that the cultural and political will align to avoid the crisis deepening further.

Plastic is a valuable resource, but it’s being wasted

We all have a responsibility to tackle plastic pollution. We are producing and using new plastic at remarkable and ever-increasing rates, and we are not dealing with it effectively.

Plastic is cheap, light, flexible, and adaptable. We use it to make things, carry things, and keep things fresh. But the amount of plastic we have made is greater in mass than all land animals and marine creatures combined. We are currently making plastic faster than ever, and due to various factors including rapid population growth and rising per capita use, the rate of plastic production is set to double by 2040.

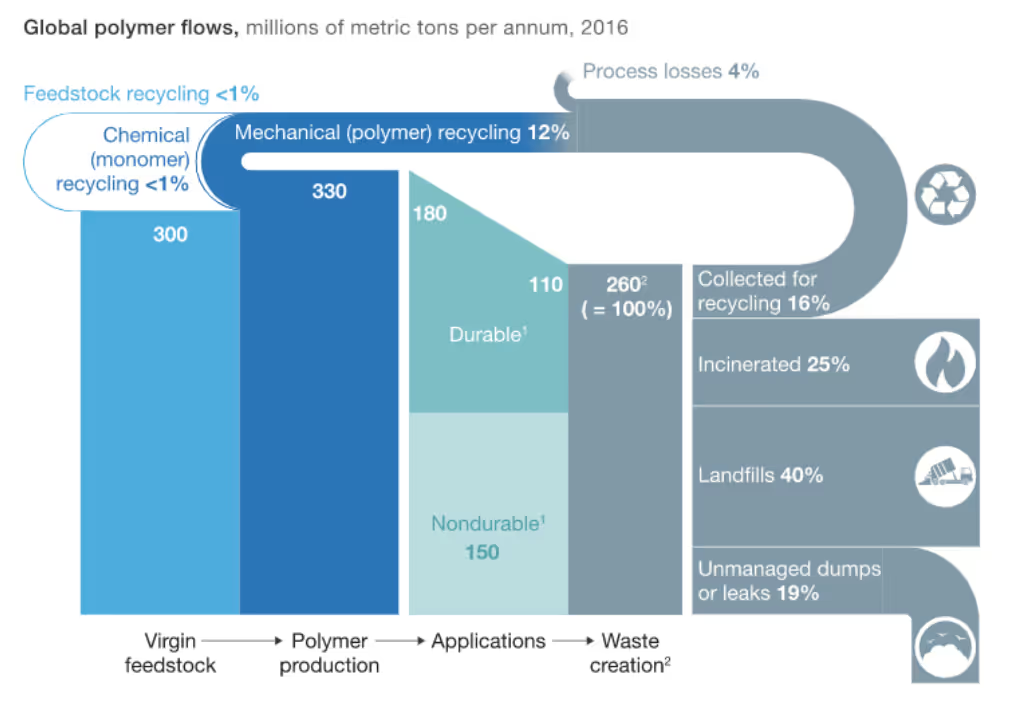

This would be less shocking if we had a more circular economy where plastic was recycled and used again. That is, currently, far from the case. Only around 12% of plastic is recycled, globally.

Current recycling and waste management infrastructure simply does not have the capacity to deal with the amount of plastic being discarded. In many areas of low-income countries, as much as 90% of waste is dumped at unregulated sites or openly burned.

Dumping of waste - including waste dumped on land – is a key contributor to ocean pollution. Almost half of the world’s population live within 100km of the coast, with wind and water often transporting materials into the sea. Rivers, particularly those running through populous areas of Asia and Africa, also carry huge quantities of mismanaged plastic into the oceans.

Plastic pollution is a global problem

But while plastic pollution might be more visible in these areas, it is not an issue limited to parts of the Global South.

The United States produces more plastic waste than any other country. Plastic footprints (amount of plastic waste per person) in the United States are, on average, five times larger than in India or China, and three times higher than in Indonesia.

Recycling plastic generally costs more than getting rid of plastic waste in “alternative ways." This results in a very small proportion of plastic in the United States being recycled domestically (~2-3% of total plastic), while a far larger proportion is incinerated. The US also exports a portion of its collected plastic waste.

Like the US, the UK has one of the highest per capita plastic footprints in the world, and lacks sufficient infrastructure or financial incentive to deal with the amount of plastic used. Where discarded plastics are collected for recycling around half is incinerated. A further 20% is sent abroad for recycling, and just 12% actually recycled in the UK.

The US and UK are by no means alone in failing to deal with their domestic plastic waste, but the fact that two of the wealthiest countries in the world are exporting plastic waste is a concern. This concern is compounded by the fact that it is being sent to countries that include India, Indonesia, Ghana and Vietnam.

Of course, it is ethically dubious to be exporting waste to countries that are facing significant waste management challenges of their own. There have also been suggestions that cheap imported plastic waste is making the situation worse by disincentivizing countries from investing in collection systems for their own plastic waste, and Thailand has recently announced a ban on plastic waste imports, from 2025.

But it gets worse. Though waste is – theoretically – shipped in order to be recycled, it has been estimated that up to 70% of plastic entering recycling facilities around the globe is discarded because it is unusable. The majority of this will inevitably end up as waste that pollutes the environment there (though Indonesia has apparently sent some rejected single-use plastic on ships back to the U.S.). It is now well documented that exports are not all recycled and often end up causing environmental harm.

In fact, taking into account the fact that significant amounts of exported plastic from the U.S. are leaking into the environment, and combining that with illegal littering and dumping on US soil, the USA may be one of the biggest global contributors to plastic waste leaking into the environment (up to 1.4 million metric tons per year ending up as plastic pollution in nature).

As a result, funding plastic waste recovery in places like India, Indonesia, Ghana and Kenya is actually quite directly addressing a pool of plastic waste that consumers and brands in the U.S, and elsewhere, have contributed to.

Plastic waste is a global health issue

Plastic waste is now polluting the whole planet. It has reached everywhere from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains. Concern is also growing about the prevalence of microplastics which have been found in food, water, air, human blood, and even breast milk.

It is not just microplastics that affect people’s health. Up to one million people die each year as a result of mismanaged waste. Waste pickers often undertake hazardous work, especially those working on illegal or poorly-managed waste dumps which can be affected by landslides and or spontaneous fires and explosions from gas build-up.

Plastic waste does not break down in nature, and ends up blocking waterways that exacerbate flooding and the spread of waterborne diseases. Burning plastic waste – and open burning is projected to triple by 2040 – contributes to air pollution, and releases toxic chemicals that affect human health.

It is, of course, not just humans that are suffering. Plastic pollution affects hundreds of marine species. It is, for example, linked to blocked digestive tracts in turtles, chemicals affecting the growth and reproduction of whale species, and entanglement of sea lions and dolphins. Evidence of plastic pollution poisoning the world’s coral reefs is also emerging.

Loss of fishing due to depleted ecosystems, and plastic ingestion by animals - including those farmed on land - also has knock-on effects for human wellbeing.

Again, there is an environmental justice issue here, with many of those contributing the least to the plastic pollution problem having to deal with the most severe consequences.

Business as usual is not going to be enough

It is pretty clear that change is required urgently to prevent these issues from worsening.

But yet, action on plastic has been slow. An international treaty on plastic waste is now being discussed by the UN, but is unlikely to be agreed until the end of 2024, and implementation will take even longer. This is despite warnings that an implementation delay of five years would result in an additional 80 million metric tons of plastic in the ocean.

There are a number of voluntary plastic pacts and various extended producer responsibility policies around the world that are attempting to address the problem. But even if all current major commitments are met, ocean plastic pollution will still double by 2040.

It is apparent from the fact that developed economies export and incinerate waste that investments in domestic recycling are required. The incentive structures that make recycling financially less rewarding than polluting have to be adjusted.

But even this investment will not stop plastic plastic leakage into nature and into the oceans. Plastic use is still on the rise. Rapid population growth and market development in some developing economies will drive up plastic use disproportionately in countries where waste management infrastructure is limited.

If we want to prevent plastic pollution from spiralling out of control, we have to look beyond business as usual – both at home and abroad.

What can we do?

Global producer responsibility

We all have a responsibility to tackle plastic pollution. Governments, businesses and individuals must all take action to move the needle on the plastic pollution crisis. Solutions are out there to prevent the crisis from escalating, and we just need to find the political will and create the right incentive structures to make progress – before it’s too late.

Is there a case for plastic waste payments to developing countries as part of this? There is undoubtedly a legacy of plastic waste from more developed countries, much of which is still bobbing about in the ocean or affecting ecosystems on land. But perhaps the concern is that the situation is at risk of becoming multiple times worse.

Acknowledging that we are part of a global problem, the real question is where and how can we invest most effectively to prevent further damage to the planet? This may well mean plastic waste producers funding action in developing countries where investments, such as creating waste management infrastructure, can have the most bang for their buck.

rePurpose Global

This relates to what we do at rePurpose Global. One of our flagship solutions is to incentivise the collection of low-value plastic waste in areas where it’s most at risk of being dumped or openly burnt. We currently run projects in India, Indonesia, Colombia, Ghana and Kenya. We do this by partnering with conscious businesses, who can take credit for funding plastic recovery and their contribution to reduced plastic pollution, as well as their support of waste workers’ livelihoods. This action on plastic waste is a powerful act, and for many brands it works as an immediate step as part of an ongoing, longer-term journey to reduce plastic use.

Of course, plastic waste collection and recovery is not the whole solution, but just one important piece of the jigsaw. Efforts are needed to reduce the growth in plastic consumption, to substitute or design plastic out of products and packaging, and to increase the recyclability of plastics already in the system.

At rePurpose Global we not only recover low-value, uncollected, nature-bound plastic through our projects, but simultaneously work with brands to build more sustainable and more circular business models. Our solutions help brands to reduce virgin plastic use, measure plastic footprints, source recycled plastic, and advocate for regional, national, and international changes.

Perhaps there was something of Giddens’s paradox at play with plastic pollution. But now it could hardly be clearer that action is needed to prevent the health of the planet being put further at risk. There can be no excuse for inaction.

Join us in this positive movement. Get in touch to find out how, working together with rePurpose Global, you can clean up the plastic problem where it is most needed, and forge benefits for climate, health, jobs, working conditions, and the environment.

.avif)