Branding and advertising are powerful tools in the environmental movement. Looking to make changes to a more sustainable lifestyle, individuals can seek out brands that align with their social and environmental values. Often, environmentally-conscious consumers pay a premium for sustainable goods, hoping that the missions purported by businesses mean we, as individuals, are taking individual steps towards a better future. But, what if a lot of what we get is actually greenwashing?

As outside pressures push businesses and corporations to contend with our growing mounds of plastic waste, many are opting for plastic alternatives marketed as compostable and biodegradable. While the companies producing these products may be transitioning to less fossil-fuel intensive materials for their plastic alternatives, these products often pose other technical and practical barriers to truly aligning with the circular economy model, and this robust ‘green’ advertising may overexaggerate the true environmental benefit of the company.

Greenwashing Plastic Alternatives: Breaking Down The Labels

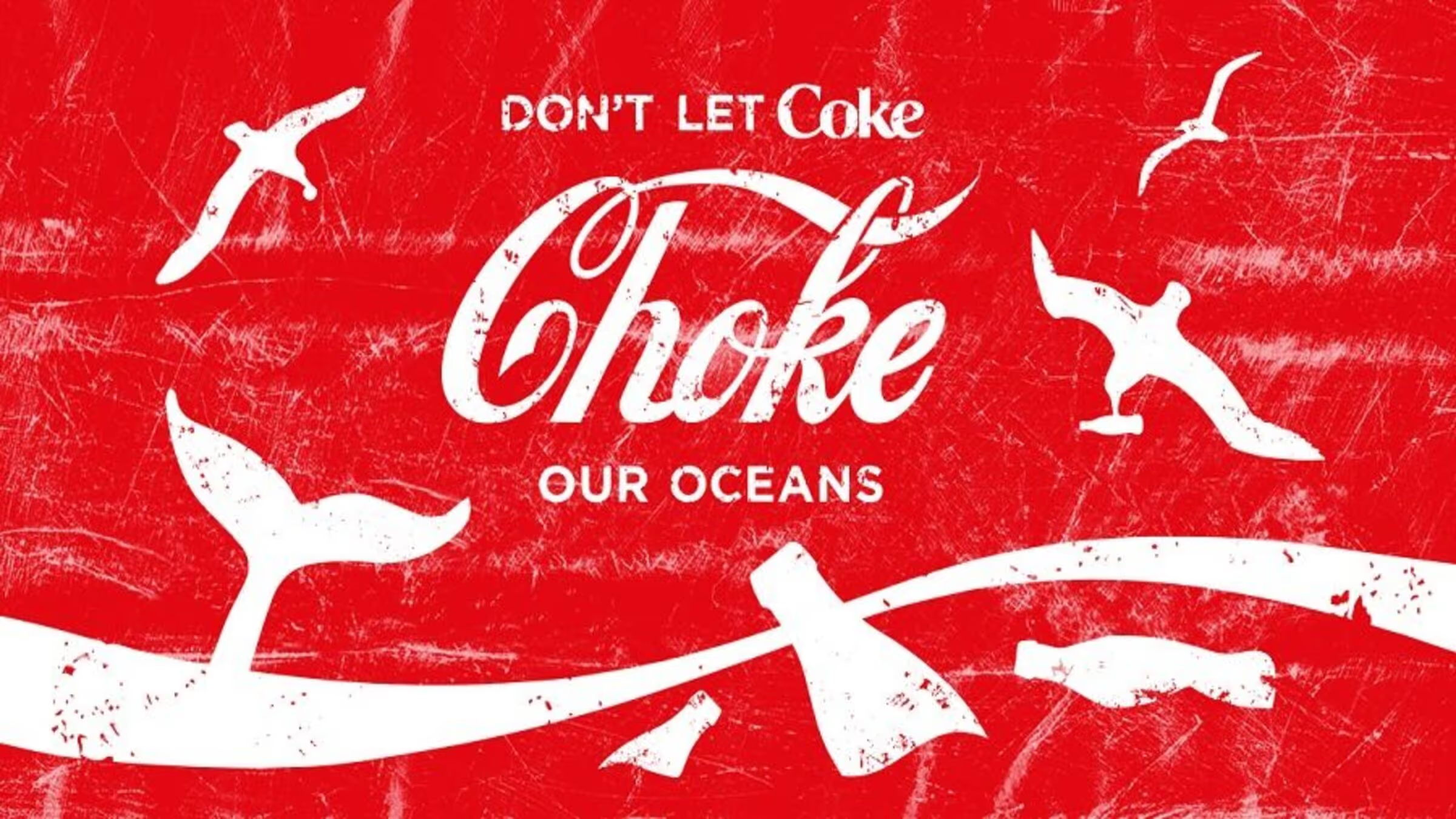

This phenomenon has been dubbed greenwashing, a blanket term that describes the pattern in which businesses mislead or deceive consumers about their environmental stewardship or promote advertising that overlooks the damages of their model while marketing themselves as sustainability progressives.

The rise of greenwashed plastic alternatives poses two primary problems. Many bioplastics earn their titles and marketing symbols by being generated from renewable, plant-based biomass (as opposed to petroleum). While the material sources of the product may be organic, this labeling promotes the idea of a product that looks and feels like plastic but breaks down naturally in the environment like organic material. Often, however, these labels indicate merely how the product was generated, not how it will break down after being used, and without the proper conditions these bioplastics will break down in the environment just as normal plastics do: they won’t.

In reality, environmental conditions will do little to expedite the breaking down of so-called compostable plastics. Most require stringent industrial conditions and mechanisms to break down, and doing so successfully requires consistent consumer access to industrial composting receptacles. Trash and recycling bins are often readily available in many US cities and municipalities today, but composting bins rarely make their way into spaces where consumers may bring their ‘compostable’ alternatives to single-use plastics. But when companies readily advertise the compostability of their products, they often fail to consider the practical lengths consumers must travel to ensure the item is not simply discarded into a landfill.

These practical barriers are common among recyclable plastic products, as well. Well-meaning manufacturers engineer plastic that complies with recycling standards, but consumers across the globe often have no way to recycle it. In many municipalities, not every type of numbered plastic is accepted, and in others, none of the plastic is at all. In these cases, manufacturers are likely not intentionally misleading consumers, but ‘recyclable’ labels likely don’t capture the probable fate of the product — after all, only nine percent of plastic produced worldwide has been recycled.

Bioplastics are attractive alternatives, offering consumers the ease of single-use plastics while seemingly alleviating some of the bad conscience associated with plastic. But its inefficiencies point to a perhaps larger flaw — not of the infallibility of our products, but of a culture of near constant use and disposal.

How Companies Perpetuate Greenwashing

Often, the danger of greenwashing lies in the powerful yet ambiguous norms of advertising.

The problem is, companies are largely given free range on their use environmental adjectives—images of leaves and recycling logos and phrases like “eco-friendly” and “natural” frequently grace the plastic-intensive packaging of everyday items. But these labels might be meaningless unless qualified — what specific initiatives is a business undertaking? By what percent are they reducing their impact, and how?

Some companies have even been known to advertise practices as sustainability initiatives when they are merely in compliance with the law, not projects that go above and beyond the status quo. Still, even this unfounded advertising can have a powerful impact on consumer choice.

Looking to help consumers make informed decisions about products, some lawmakers in California are cracking down on greenwashing. In one case, California Attorney General Kamala Harris filed a suit against a water bottle company, Aquamanta, that claimed to carry biodegradable bottles. Their use of the term ‘biodegradable’ was shown to be unsubstantiated, and sales of the product promoted deceptive or misleading marketing claims.

In another California case (Hill v. Roll International Corporation and Fiji Water Company LLC), a water bottling company was sued over their claims of providing “environmentally friendly and superior” water. The company was in fact found to use a “greater amount of natural resources” in the production and distribution of their bottled water than their competitors, with an impact of 46 million gallons of fossil fuel a year, equivalent to 216,000,000 billion pounds of greenhouse gases.

To expect corporations to practically eliminate their environmental footprint overnight is a far-fetched goal. And to promote an economy that favors sustainable alternatives, it can be helpful to celebrate even small improvements. Greenwashing But consumers cannot support firms that merely advertise their sustainability, but more importantly, those that have shown their commitment on the ground to improve their products.

Small steps enable big changes, take yours today. Curb your own plastic consumption and mitigate your negative impact on the planet by going Plastic Neutral with us today.

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)